In this session you will explore how many of the innovations of the First World War have impacted on medicine today.

Harry Brearley was born in Sheffield in 1871. He was the son of a steelworker. He left school at 12 years old and became a labourer at the company where his father worked. Harry worked hard and was promoted to the position of general assistant in the company’s chemical laboratory. He took evening classes and learned how to specialise in steel production techniques and chemical analysis. By the time Harry was in his early thirties, he had a good reputation in his chosen industry.

In 1908 two of Sheffield’s largest steelworks combined to launch a new research laboratory. Harry was asked to be the lead on the project.

In 1912, a weapons manufacturer asked Harry to produce a metal that would not be damaged by heat or corrode. As a renowned metallurgist, Harry began researching new steels that would not erode at high temperatures. After months of experimenting with adding chromium to steel, Harry created a new alloy that was resistant to chemical attack. He called this new discovery ‘rustless steel’.

The discovery revolutionised the metal industry and became a key part of the modern world. Coming from Sheffield, known as the ‘Steel City’, Harry was excited at this discovery and saw the potential for the new metal to be used in other objects as well as military weapons.

Today, stainless steel is used to manufacture many different products including those used for medicine, such as surgical instruments.

The company Kimberley Clark had been searching for a material that was more absorbent than cotton but cheaper to make and they invented a material called Cellucotton before the First World War. When the US entered the First World War in 1917, they began using Cellucotton to make wadding for bandages. Red Cross nurses on the battlefield realised the benefits of the material for their own personal hygiene and it was this unofficial use that made the company’s fortune.

The British Army began treating wounded soldiers with blood transfusions by directly transferring blood from one person to another. It was Captain Oswald Robertson, a US Army doctor, who realised the need to store blood before the injured arrived. He established the first blood bank on the Western Front in 1917. He used sodium citrate to stop the blood clotting and becoming unusable.

Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae was a Canadian poet and physician during the First World War. He was working as a surgeon during the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium in 1915 when a friend of his died. His burial inspired McCrae and he wrote the famous war memorial poem ‘In Flanders Fields’.

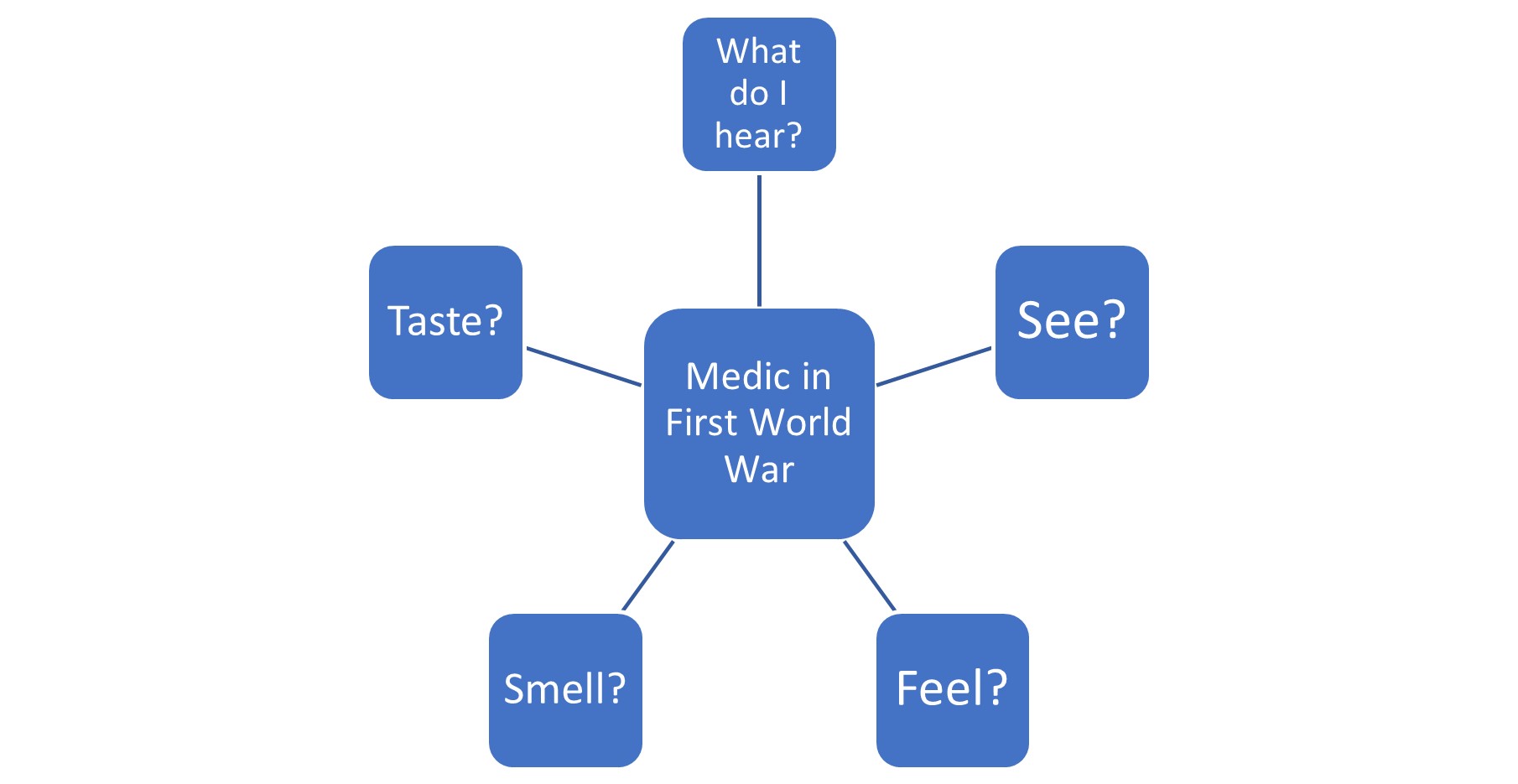

Put yourself in the place of a medic on the front line during the First World War. Complete the spider diagram to think about what you see, hear, feel, smell and even taste around you. Use this to write a short poem of your experiences.

In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead, short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

Well done! You have completed your final Medicine in the First World War session. Now, why not discover more about how different nations worked together in the Second World War.